The Anthropological and Moral Dimension

The right to a healthy environment and ethical-political responsibility in the management of plastics

By Paolo Gomarasca, Full Professor of Moral Philosophy

Introduction

The use of plastic has profoundly transformed modern societies, making everyday life more convenient and accessible. However, its environmental impact raises ethical and political issues of paramount importance. Resolution 48/13 of the United Nations Human Rights Council enshrined the human right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, highlighting the need for concrete commitment to pollution management. In this context, Resolution 5/14 of the United Nations Environment Assembly proposes legally binding measures to combat plastic pollution.

This note analyses the role of plastics from an anthropological, ethical and political point of view, examining the responsibilities necessary to ensure environmental sustainability. The cultural implications of the use of plastics, the legal implications and governance models for dealing with this global crisis will be discussed.

1. Plastic as a Cultural and Ethical Phenomenon

Roland Barthes described plastic as a "myth" of modernity, capable of taking on infinite forms and functions. In Mythologies (1957), Barthes writes: "More than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation, it is, as its vulgar name indicates, ubiquity made visible; And precisely in this, on the other hand, it is a miraculous matter: the miracle is always an abrupt conversion of nature. The plastic is all impregnated by this shock: more than an object, it is a trace of a movement." This concept reflects plastic's ability to be molded into a variety of objects and shapes, representing the ideal of adaptability in industrial society. However, Barthes also emphasized the artificial and inauthentic character of plastic, hence its intrinsic ambivalence, stating that "the price of its success is that plastic, sublimated as a movement, hardly exists as a substance. Its constitution is negative: neither hard nor profound, it must be content with a neutral substantial quality in spite of its utilitarian advantages: it knows resistance, a state that supposes the simple suspension of an abandonment, In the poetic order of great substances it is an ungainly material, lost between the effusion of rubber and the flat hardness of metal: it does not reach any true product of the mineral order, foam, fibers, layers. It is a substance gone bad: to whatever state it is reduced, plastic retains a flaky appearance, something cloudy, creamy and frozen, an inability to achieve the triumphant smoothness of nature. And most of all, it is betrayed by the sound that comes out of it, empty and flat at the same time; its noise undoes it."

The history of plastic began in the 19th century, with the discovery of parkesin by Alexander Parkes in 1856, the first semi-synthetic plastic material. The real turning point came in 1907 with the invention of Bakelite by Leo Baekeland, a fully synthetic material that marked the beginning of the era of modern plastics (Meikle, 1995). World War II accelerated the production of new polymers such as nylon and polyethylene, key materials for the war industry and later for the civilian sector (Freinkel, 2011).

Already during the war and then, increasingly, in the post-war period, plastic became the symbol of consumerism and technological progress. Plastic has indeed embodied the optimism of the modern era, a cheap, versatile and seemingly inexhaustible material (Andrady & Neal, 2009). It is no coincidence that, in 1941, cartoonist Jack Cole created Plastic Man, a superhero capable of imitating any other form, as if to celebrate the potential of this innovative material, which was beginning to spread in America.

The term plastic, in fact, derives from the Greek plassein, which means to shape a soft substance and refers precisely to the ability of this material to be shaped into a specific shape.

However, its environmental impact became apparent as early as the 1970s, when researchers began reporting the presence of plastic waste in the oceans (Carpenter & Smith, 1972).

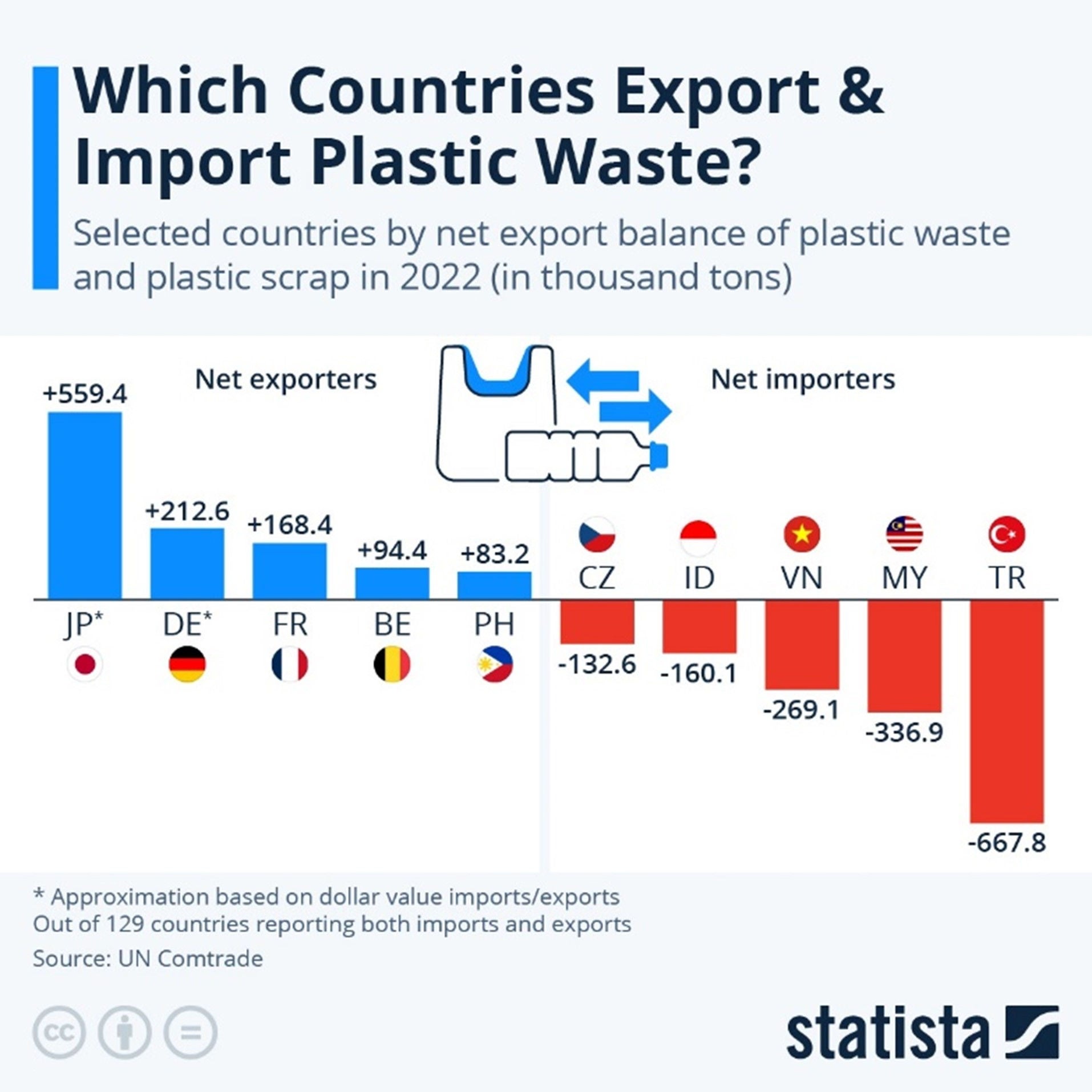

The production and consumption of plastic therefore raise ethical questions related to environmental justice, also because the damage resulting from plastic pollution disproportionately affects vulnerable communities (Thompson et al., 2009), to the point that we have begun to speak of "waste colonialism", considering the amount of tons that the North of the world dumps to the South, especially in the Asia Pacific area (Cayli Messina, 2023).

According to a recent study, microplastics are contaminating food chains and directly affecting human health, leading to potential biological hazards that are still poorly understood (Smith et al., 2021).

2. The Human Right to a Healthy Environment and Resolution 48/13

UN Human Rights Council Resolution 48/13, adopted on 8 October 2021, clearly states that "the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a fundamental human right" (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2021). This declaration emphasizes the correlation between environmental degradation and human rights, emphasizing how the ecological crisis directly threatens the right to health, life and well-being of global populations:

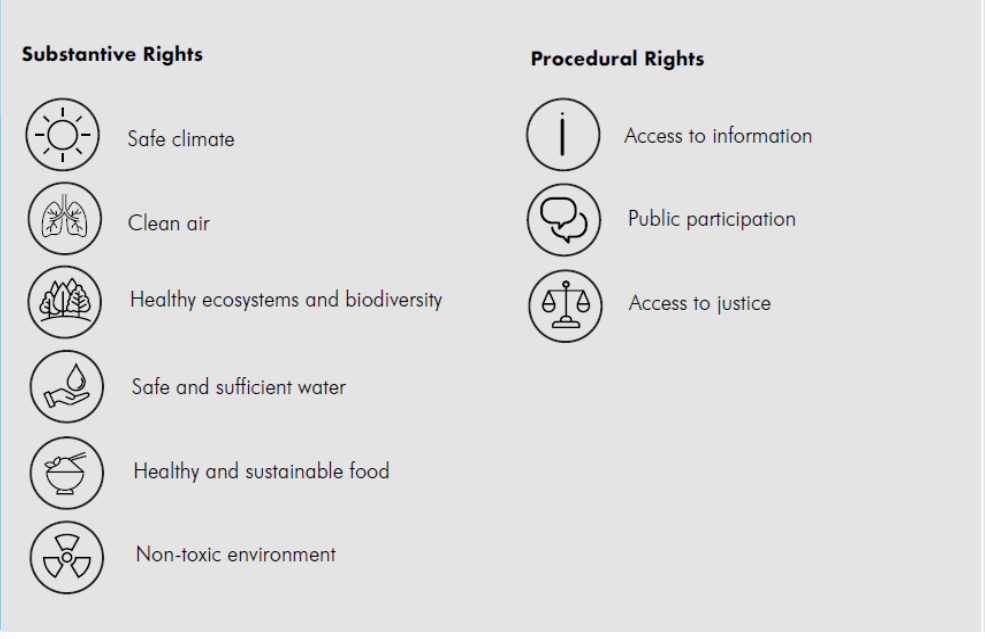

In the official document, the Council recognises that the negative impacts of climate change, unsustainable management of natural resources and pollution undermine the full enjoyment of human rights. Although there is no universally agreed definition of the right to a healthy environment, it is generally understood to include substantive and procedural elements. Substantial elements include: clean air; a safe and stable climate; access to safe water and adequate sanitation; healthy, sustainably produced food; non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play; as well as biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. Procedural elements include: access to information, the right to participate in decision-making processes, and access to justice and effective remedies, including the safe exercise of these rights without fear of retaliation or reprisals (UNEP, OHCHR, UNDP, 2023).

The realization of the right to a healthy environment also requires international cooperation, solidarity, and equity in environmental actions, including the mobilization of resources, as well as the recognition of extraterritorial jurisdiction for human rights harms caused by environmental degradation.

That is why the resolution calls on all Member States to strengthen multilateral cooperation, increase technical assistance and support international initiatives to ensure a healthy environment for all.

This resolution has profound implications for environmental governance, as it imposes an obligation on Member States to take appropriate measures to reduce pollution and protect natural ecosystems. In addition, it stresses the need to provide resources and support to developing countries, which often face the most serious consequences of environmental pollution, without having adequate tools to combat it (Kashwan, 2022).

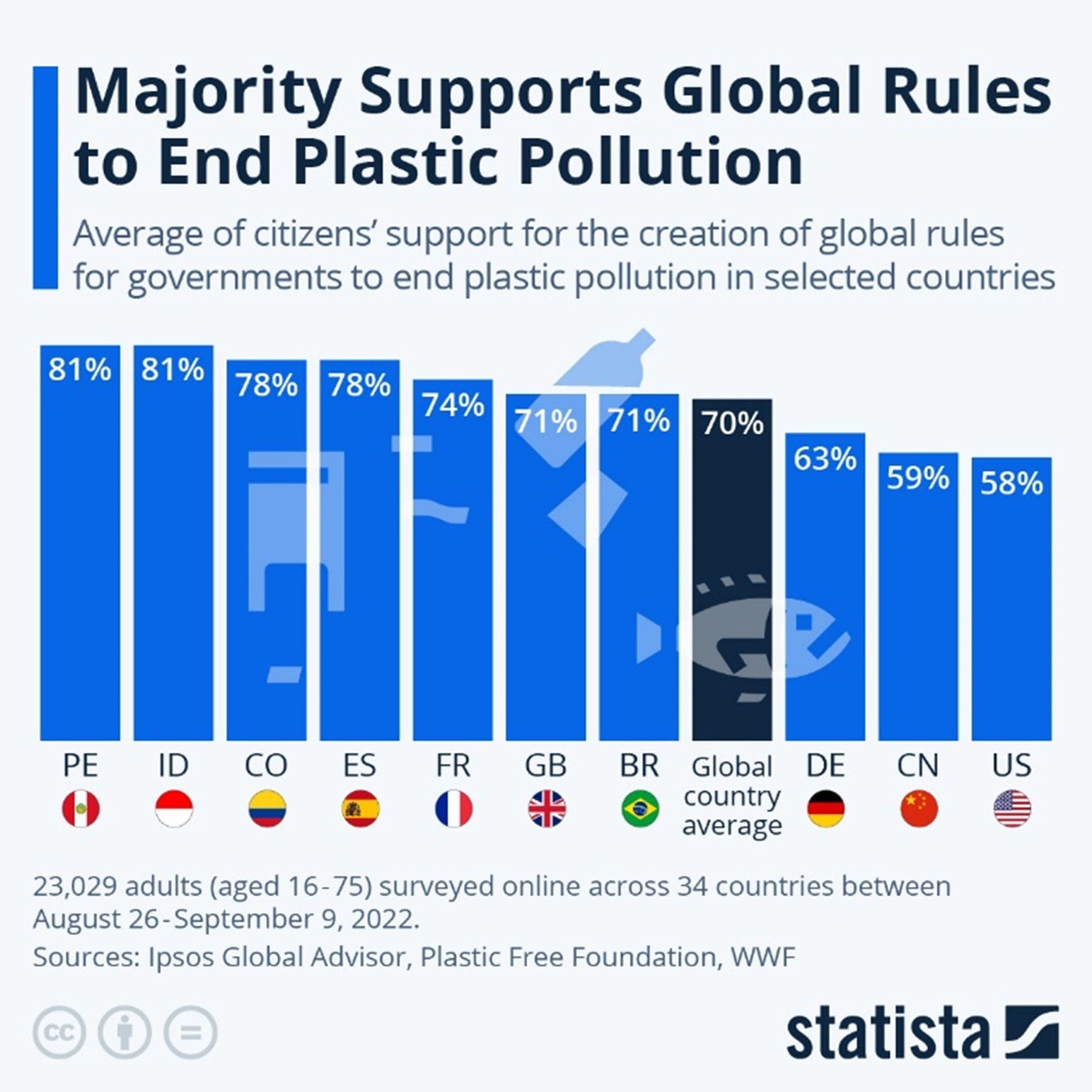

Finally, Resolution 48/13 also highlights the need to involve civil society, businesses and governments in concerted action to ensure environmental protection. Environmental governance must be participatory, transparent, and evidence-based to effectively address the challenges of plastic pollution (UNEP, 2021). After all, the majority of citizens are now increasingly convinced of the need to establish global rules, especially in relation to tackling and combating plastic pollution.

3. International Policies and Regulations: Resolution 5/14

Resolution 5/14 of the United Nations Environment Assembly, adopted on March 2, 2022, recognizes the need for a legally binding international instrument to tackle plastic pollution. According to the text of the resolution, plastic pollution has reached unprecedented levels and poses a direct threat to biodiversity, food security and human health (UNEP, 2022). The beginning of the resolution does not hide the concern, but at the same time it does not renounce, on the contrary, it strongly affirms the need and possibility of an ethical change and calls for an essential strengthening between science and politics:

"Noting with concern that high and rapidly increasing levels of plastic pollution represent a major environmental problem on a global scale, with negative impacts on the environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainable development,

Acknowledging that plastic pollution includes microplastics,

Noting with concern the particular impact of plastic pollution on the marine environment,

Noting that plastic pollution, in marine environments and other ecosystems, can be transboundary in nature and that it needs to be addressed, along with its impacts, through a whole life cycle approach, taking into account national circumstances and capacities, [...]

Stressing the urgent need to strengthen the interface between science and policy at all levels, improve understanding of the global impact of plastic pollution on the environment, and promote effective and progressive action at local, regional and global levels, recognising the important role that plastics play in society, [...]

affirming the urgent need to strengthen global coordination, cooperation and governance to take immediate action aimed at the long-term elimination of plastic pollution in marine environments and other ecosystems, avoiding damage to ecosystems themselves and human activities dependent on them.

Acknowledging the wide range of approaches, sustainable alternatives and technologies available to address the entire life cycle of plastics, further highlighting the need for enhanced international collaboration to facilitate access to technology, capacity building and scientific and technical cooperation, and stressing that there is no one-size-fits-all approach,

Emphasizing the importance of promoting the sustainable design of products and materials so that they can be reused, regenerated or recycled and thus kept in the economy for as long as possible, together with the resources from which they are composed, and to minimize the generation of waste, contributing significantly to the sustainable production and consumption of plastics." (UNEP, 2022)

This resolution calls for the creation of a binding international treaty by 2024, including measures to reduce plastic production, improve waste management systems, and promote the circular economy. "Plastic pollution is a global crisis that requires internationally coordinated solutions" (UNEP, 2022). The resolution states that member states must ensure compliance with the principle of extended producer responsibility (EPR) by incentivising sustainable design practices and investing in advanced recycling technologies.

Conclusions

Plastic represents one of the most pressing environmental challenges, requiring synergistic action between international regulations, national policies and individual behaviors. Resolution 48/13 and Resolution 5/14 provide an essential framework for guaranteeing the human right to a healthy environment. The transition to a sustainable model is a collective responsibility, founded on ethical and political principles that aim to preserve the planet for future generations.

Insights

- Andrady, A. L., & Neal, M. A. (2009). Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1526), 1977-1984.

- Bartes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Translated into English by Richard Howard and Annette Lavers as Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang , 2012)

- Boyd, D. R. (2021). The Human Right to a Healthy Environment. Cambridge University Press.

- Cayli Messina, B. (2023) Environmental Injustice and Catastrophe: How Global Insecurities Threaten the Future of Humanity, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Carpenter, E. J., & Smith, K. L. (1972). Plastics on the Sargasso Sea surface. Science, 175(4027), 1240-1241.

- Freinkel, S. (2011). Plastic: A Toxic Love Story. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Meikle, J. L. (1995). American Plastic: A Cultural History. Rutgers University Press.

- Smith, O., Brisman. (2021). A. Plastic Waste and the Environmental Crisis Industry. Crit Crim 29, 289–309 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-021-09562-4

- Thompson R.C., Swan S. H., Moore C. J. and vom Saal F. S. (2009). Our plastic age. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1973–1976 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2009.0054

- United Nations Human Rights Council. (2021). Resolution 48/13.

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2022). Resolution 5/14.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2023). What is the Right to a Healthy Environment? - Information Note. https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/what-right-healthy-environment-information-note